Blogpost: A Perspective on Transdisciplinary Praxis

There have been decades of debates, especially in academia, about the benefits and successes of disciplinary vs. non-disciplinary or transdisciplinary education and research1. Psychologist Jean Piaget, who is considered to have coined the term transdisciplinary, was envisioning a space of knowledge beyond the disciplines 2 3. This kind of space allotted to work with/in multiple disciplines should be seen as vital in a time when one can see categories and intersections closing in on themselves. When professionals no longer understand the other, communicate with the other or see the value in the other, we are on the verge of a great loss.

This article investigates what transdisciplinarity means within artistic praxis. Obviously, there is much more to it than the initial bafflement that spreads across one’s face when first hearing the term “Transdisciplinary Artist”. Often followed by the question “But do you paint or sculpt?” Western cultures adore putting professions into their appropriate categories, clean and orderly, boxed up disciplines. The transdisciplinary artist breaches these boundaries; an outsider, a transient, a stray, which nomadically asserts space within several disciplines.

In her work on human-animal ethics in the anthropocene, Barbara Creed states of strays that “When a creature seems not to belong to a clearly definable species, she becomes a stray, a being without kin” 4. It is easy to consider this when looking at the position of transdisciplinary artists.

Moss-Butt Specimen: a piece of sphagnum moss separated from the bog carpet and rooted directly into a cigarette butt, Slåttmossen Nature Reserve, 2021.

When it comes to acts of straying there are those who jump to censor, restrict and protect the boundaries of disciplines, and the current art market by thrusting up walls against trespassers of regulated professions. Yet, from our perspective the artist holds a unique position, the artist is not only allowed but expected to push against the limitations and breach the boundaries set by current ideology. The artist is given special privileges to experiment in poly-discipline-amorous modes which others are not allowed to, due to regulatory bodies or professional standards of conduct. Transdisciplinary praxis allows space for disciplinary strays to test, destabilize and denaturalize current categorical-discourse, and the positioning of the self within them. That freedom to wander that every artist is seeking is found in straying from normative systems and narratives.

It is important to note that these special privileges come with certain expectations and responsibilities. As transdisciplinary practitioners we have an obligation to respect the disciplines we negotiate within. Transdisciplinary work must remain attuned to the research practices of other disciplines, keeping legitimate ties and comprehensibility, while negotiating new avenues of methodology, all the while remaining an undutiful stray to all disciplines.

[…] research-creation challenges reigning academic cultures less by asserting a new, disciplined and disciplining, academic identity, a noun (the artist-researcher), than by offering us something verbified and vertiginous, something that queers normative university discourse, propagating uncanny academic kinship structures and unexpected disciplinary intimacies and alliances.[…] It requires that one cultivate a robust capacity to follow curiosity and sit with anxiety. And it requires that one navigate multiple pulls across disciplinary sites, methodological approaches, and formal requirements.

Natalie Loveless, 20195.

The artist is an accepted stray within society and the transdisciplinary artist is a stray even to the standards of the “art profession” itself; the bizarre, the abstract, the ECCENTRIC!

Cigarette Butt Fieldwork: butts are absorbed into the bog and regurgitated back out as the bog deflates, churns, and heaves with the seasons, Slåttmossen Nature Reserve, 2021.

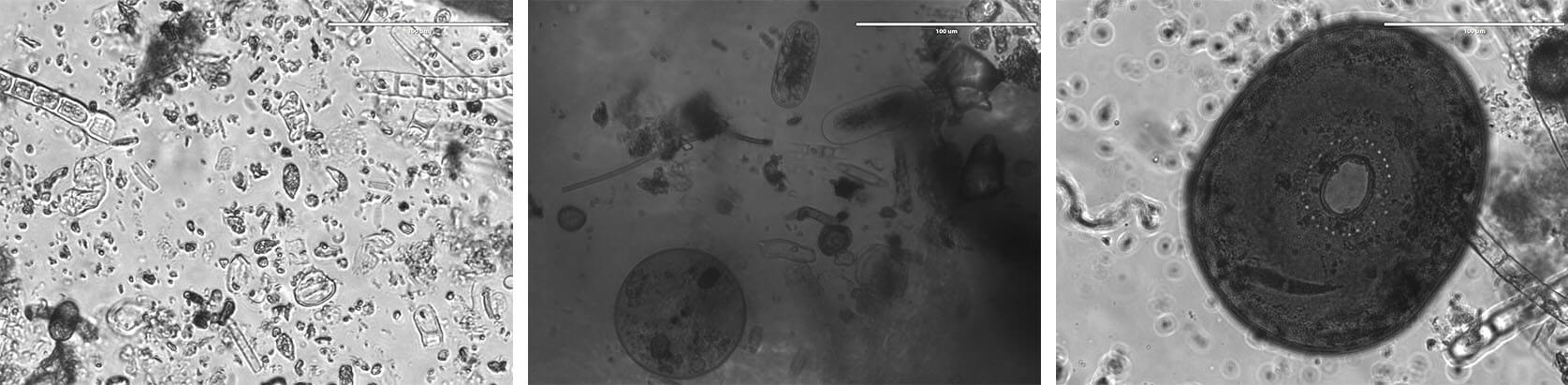

The chosen images for this article are taken from the Master of Arts thesis work (ViCCA-programme, Aalto-ARTS) by Cynthia Blanchette, which investigates the concept of stray and its relation to a bog. The project focuses on a tiny nature reserve called Slåttmossen on the outskirts of Helsinki. Blanchette’s thesis consisted of theoretical work, practice-based work, documentation of hands-on experimental fieldwork, such as a weekly practice of documenting bog happenings, picking cigarette butts from the bog as evidence and collecting samples of microscopic life to be observed under a microscope. It also included experiments in transferring bog-fragments to a textile and a bog-stray rescue operation. This multifaceted project culminated in a wearable system, a kind of uniform, designed to protect the boundaries and porosities of both the human body and the bog terrain during encounters. This artifact, the uniform, delves into a complexity of concepts, such as power, control, domestication, protection, safety, care, porosity, and also environmental justice - in a comparable manner to how societal and cultural categories defined borders, regulations and expectations are constructed. Additionally, Blanchette developed and wove the bog camouflage textile for her uniform with a pattern based on a microscopic image of human macrophage cells which help eliminate foreign substances from the body by engulfing them.

In her work Blanchette often uses the term porous in multiple contexts, from human skin and human activity to wetlands being inherently porous, and further, in her position as an artist, who leaves the narrative open to those who come across the uniform Porous-Boundary System to create their own stories 6. Furthermore in relation to porosity and transdisciplinary artistic praxis one can ask: is it possible to rebuild relations through porous-praxis to create a context in which there are no strays, and disciplines are inclusive and merging?

Microscopic Life in Water Samples: bacteria, plant cells, protozoa and microscopic animals mixing, procreating and thriving off of each other’s life and death, Slåttmossen Nature Reserve, 2021.

As no single practice has all the answers; one can claim that the value of transdisciplinary praxis is in the ability to perceive issues from more than one perspective, to create connections between disciplines and stir the ground between the fields, revealing that which ties diverse fields, perspectives and approaches together.

And resistance is emerging in many places, in many ways. We must experiment.

Françoise Vergès, 20207.

Porous-Boundary System, Cynthia Blanchette, 2021.

-

Darian-Smith, E. & McCarty, P. (2016). “Beyond Interdisciplinarity: Developing a Global Transdisciplinary Framework.” Transcience, 7(2): 1-26. ↩︎

-

Piaget, J. (1972). The Epistemology of Interdisciplinary Relationships. In: L. Apostel, G. Berger, A. Briggs and G. Michaud ( eds.) Interdisciplinarity: Problems of Teaching and Research in Universities (pp.127-139). Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. ↩︎

-

Nicolescu, B. (ed.) (2008). Transdisciplinarity - Theory and Practice. Hampton Press, Cresskill, NJ, USA. ↩︎

-

Creed, B. (2017). Stray: Human-Animal Ethics in the Anthropocene. Power Publications. Apple Books. p.137. ↩︎

-

Natalie, L. (2019). How to Make Art at the End of the World: A Manifesto for Research-Creation. Duke University Press. p.57. ↩︎

-

Blanchette, C. (2021). Strayscapes: Porous Boundary Making Through the Eye of the Bog. Aaltodoc. http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:aalto-202111019949 ↩︎

-

Vergès, F. (2020, January). Interview by T. Gerber. A Decolonial Feminism: Timofei Gerber in conversation with Françoise Vergès. Epoché Magazine. 28. https://epochemagazine.org/28/a-decolonial-feminism/ ↩︎